Hollywood owes more to opera than it would ever admit. At cinema’s beginnings, the pioneers were more interested in developing the new technologies and selling the hardware than they were in building a library of what we would now call content.

Thomas Edison had the Black Maria Studio that he charged with finding uses for his new invention, the Kinetoscope. The studio developed celluloid loops containing thirty second motion picture entertainment to be partnered with phonographic recordings. When he showcased his new invention in 1893, many of Edison’s Kinetoscope movies showcased popular vaudeville acts.

In France, the Lumière brothers gave the first commercial screening of their Cinématographe in 1895 for which they filmed actuality films such as Workers Leaving The Lumière Factory. They also included a staged mini-comedy called L’Arroseur Arrosé. For its naturalism and simplicity it’s worth a look on YouTube. The Cinématographe was an instant hit and made the Lumières rich overnight.

In the beginning, people were drawn to the novelty of the invention. It wasn’t long before the novelty wore off and the pioneers had to find new material to keep people buying tickets. An echo of the gold rush rang around inventors in both the United States and Europe with the result that the new technology developed fast.

Soon Edison remarked “With each succeeding month new possibilities are brought into view. I believe that in coming years by my own work and that of Dickson, Muybridge, Marié (all worked in his studio) and others who will doubtless enter the field, that grand opera can be given at the Metropolitan Opera House at New York without any material change from the original, and with artists and musicians long since dead.”

He imagined that opera could be presented with the visuals being projected onto a screen and the sound being captured phonographically and that somehow this would be as satisfying for the Metropolitan audience as the real thing. At the end of the C19th, opera was thought to be the highest form of theatrical entertainment and its stars were as famous in their time as film stars are today.

In the frenzy to capture material that may be of interest to ticket buyers, the new cinematographers set about filming operas. The static nature of the staging worked well with the fixed nature of the tripod cameras being used to capture the images. In 1900, Clément Maurice, a protégé of the Lumière brothers, exhibited film footage of Victor Maurel singing arias from Don Giovanni and Falstaff as well as Emile Cossira performing an aria from Roméo et Juliette at the Paris Exhibition.

In 1901, Robert W. Paul’s film “Scrooge, or Marley’s Ghost” was notable for inter-titles – card inserts on the film providing narration and dialogue.

Inter-titles paved the way for longer scenes and in 1907 British Gaumont released Gounod’s opera, Faust, in full. There was still no recorded sound for these films and any music would have to be provided live by an improvising pianist in order to synchronise.

In 1904, the Metropolitan Opera’s production of Parsifal was filmed by Edwin S. Porter, another Edison employee. At the time, Parsifal was still a global hot ticket, having only been performed at Bayreuth to that point. Anyone who had seen Parsifal at Bayreuth, talked about it with a religious zeal and cognoscenti everywhere who had not seen it were eager to do so. To film and present it made good business sense.

Wagner’s widow, Cosima, tried to prevent the filming of Parsifal but Marlen Merry acquired the rights and Porter went ahead anyway. Edison had been experimenting with ways to combine silent film with recorded music. Porter used Edison’s Kinetophone for his Parsifal of which Opera Quarterly’s Solveig Olsen wrote, “a primitive, synchronized sound-mix device, but this machine does not represent the end of the era of silent film, since it had a short life with no great success.”

After the Great War, Enrico Caruso, the biggest global star of the day, was cast in two silent films, My Cousin (1918) and The Spendid Romance (1919).

In 1926, Robert Weine created a film of Richard Strauss and Hugo von Hofmannsthal’s opera, Der Rosenkavalier, originally premiered in 1911. Hofmannsthal wrote new scenes for the screenplay and Strauss arranged the film score for orchestra alone, adding new music. The footage added scenes shot in the countryside, lending a context of pure rural Austria versus the moral decay of urban Vienna embodied by Baron Ochs.

Watching it, we see how the two mediums of opera and film bonded to create what we now think of as melodrama. The exaggerated stagy make-up, lingering moody shots of female protagonists and static scenes in which dialogue is implied but the actors, like marionettes, are mute while inter-titles tell us what’s going on. Interestingly, the Octavian is played by a young male actor as opposed to the role being taken by a female playing a pubescent young man in the opera.

Der Rosenkavalier is a fascinating document of how music came to be the life-blood of film, imbuing it with drama, intimacy and scope. A decade later, Max Reinhardt lured the Viennese prodigy, opera composer Erich Korngold, over to Hollywood to arrange Felix Mendelssohn’s incidental music for his film adaption of A Midsummer Night’s Dream, recently a success on stage at the Salzburg Festival. The Warner Brothers assigned every in-house star to the project and it was a hit. Korngold was taken on by the studio, going on to write many dynamic scores for the swashbucklers starring Errol Flynn, the box office staples of the time. With Captain Blood, Robin Hood, The Private Lives of Elizabeth and Essex, The Sea Hawk and The Sea Wolf Korngold established himself as indispensible for guaranteeing success at the box office.

Soon, all the musical talent was being drawn away from the opera houses of Europe and over to Hollywood where the studios were fast becoming global brands. They were attracted by the glamour and the financial rewards promised by what was fast becoming mass-produced opera, namely film.

The link between opera and film stretched well into the C20th. Sergio Leone said of his trilogy of A Fistful of Dollars, For A Few Dollars More and The Good, The Bad and the Ugly that they were filmed to be “operas in which the arias are sung by the eyes”. Leone’s school friend from their youth in Rome who had gone on to be a composer, Ennio Morricone, provided the film score.

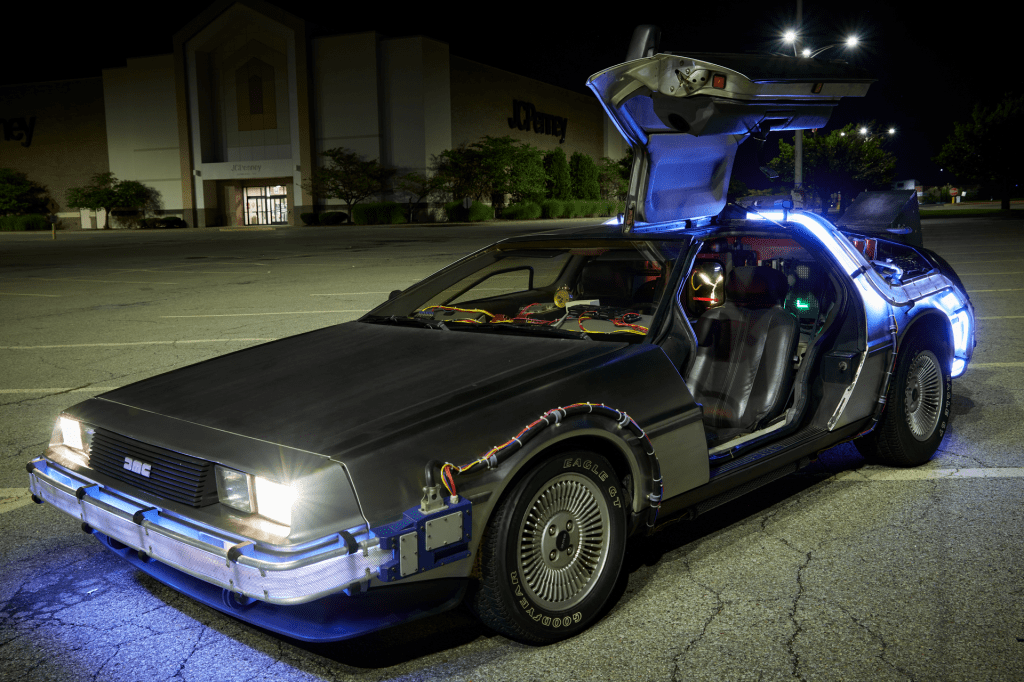

In the ‘70s, perhaps the most intriguing blend of operatic dramaturgy and Hollywood technology hit the big screen: George Lucas launched his hugely successful series of films, starting with Star Wars. The film was a blatant adaption of Mozart’s Die Zauberflöte (The Magic Flute). Lucas himself termed his new film “a space opera”.