On the podium, the conductor is responsible for all the decisions made during the rehearsals regarding shaping, tempo, balance, silences. Unilateral decisions by players on the give and pull of phrasing or space for taking a breath can lead to surprises which in turn can lead to a loss of ensemble, or togetherness. The conductor’s job is to get the best from the musicians while realising his or her ideas for how a piece of music should sound and be shaped.

As Sir Charles MacKerras once said: “The whole art… is to will the interpretation he wants and that the players submit willingly to it.”

Ensemble

The most important role of the conductor is to keep the orchestra playing together. Detailed preparation of the score and clarity in their conducting technique are vital to achieve good ensemble. An organised rehearsal process enables the orchestral players to feel comfortable with the music. Identifying challenging passages of the music and repeating them until the players feel confident is part of the process.

The last point seems obvious but I am occasionally surprised when a conductor runs out of time in a rehearsal and passages that need repeating are left to a wing and a prayer for the performance.

Musical phrases are subdivided into bars. The metre of the music, like poetic metre, is ordained by the number of beats in a bar. A bar can have any number between one and twelve beats in it. For every number of beats there is a pattern the conductor can show with their baton for the musicians to orientate where they are in any given bar. Generally speaking, the first beat, called the downbeat because the conductor indicates it with a downward movement of their baton, has the most emphasis.

Diplomacy

Mistakes can happen. Conductors have to judge which mistakes are worth letting go by without correction in rehearsal. Too much stopping and starting to correct small, acknowledged mistakes will waste precious time and eat into the orchestra’s will to work. Psychologically, orchestras are both a unanimous union and a crowd of individuals. The politics between the players are ever present in rehearsals and every orchestra has a member whom the other players think lets the side down.

Conductors require the acumen to navigate the practicalities of the work in hand without being drawn into the politics of the orchestra.

Calm

If the conductor is relaxed, it’s easier for everyone else to be in control. Like everyone, musicians produce their best work when they are focused and calm.

Some conductors breathe instinctively with the music, making the preparation and shaping of a phrase organic for singers and instrumentalists alike.

In performance it must be the hardest thing for a conductor to remain composed if something goes wrong. They have to keep going and they can’t disturb the music by speaking directives. They have to maintain their place in the score, keep going at the same pace and try to indicate to those who are out of kilter how they can get back into step with everyone else. It can happen.

Slip-ups can be distracting for many pages of music after the mistake has been made. For inexperienced conductors and performers it can set off a cascade of emotions from embarrassment to regret to anger to giggles. If we don’t put it behind us the emotions can contaminate a whole performance. Experience and discipline helps to put the slip out of our minds, only to be revisited for any lessons to be learnt after the performance.

I remember a performance of Britten’s War Requiem when the conductor indicated to a percussionist to play the bell at the very beginning of the work. Nothing happened. He had to keep going and immediately indicate for the tenors in the choir to sing “Requiem”. The very experienced conductor (no names, obvs) said “F**king bells!” loud enough for it to drown out the tenors in the choir.

Imbuing calm is like sprinkling magic dust on the performance. It can lead to “flow”, a state in which the music seems locked into a timeless, disembodied, almost spiritual state. It’s rare but when it happens it’s very special.

No-nos

The conductor’s job is to get the best reading of a work out of their players. Through silent means they have to conjure harmonious sound from a team of individuals. Below is a short list of bad habits conductors can develop that help no-one, least of all the music.

Knee bending

Bouncing on the knees in time with the music can make the music heavy and the conductor finds it harder to achieve a nifty shift in gear where it might be required. The greats all stand on straight legs and show tempo through their hands. Günter Wand, Colin Davis, Roger Norrington were some of the masters of this.

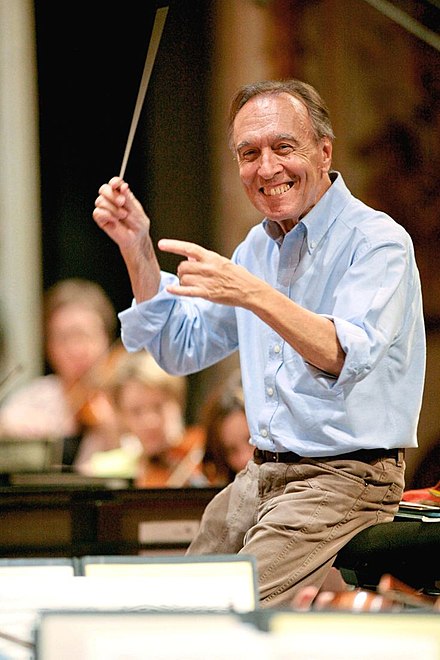

Loud conducting

It must be so tempting for a conductor to move like they’re generating the sound. A wild, flailing beat of ecstasy can look impressive to non-musicians but to musicians it looks indulgent and unnecessary. I find it distracting. Great conductors know how to release the sound they want from an orchestra without dancing for it. Bernard Haitink was a model of nobility on the podium and his music never lacked excitement.

Stop beat

When a conductor wants to be emphatic or when things are going awry, the beat can take on a staccato, stop-go quality. For calm orientation and a keen sense of tempo, there’s no substitute for keeping the baton moving. The smoother the better. A beautiful shape to the beat creates beautiful music. Look at Riccardo Muti and Carlos Kleiber for their elegant stick technique.

Top heavy

Being over conscious of the movement in the upper torso and arms can make the arms spidery and chaotic. The cause often comes down to blocking the breath. By breathing naturally, conductors root their movement low in the abdomen, enabling the conductor to relax the shoulders. When the shoulders drop the beat becomes embodied and organic. Günter Wand and Yevgeny Svetlanov were paragons of a centred technique.

Head down

Relying on the score and having the head buried in it betrays insecurity. If the conductor can’t look at the players, how can they expect the players to look at them?

Eye contact with the players is paramount. The more familiar conductors are with the score, the less they have to look at it. Some conductors specialise in memorising scores – Gustavo Dudamel must have an eidetic memory. It liberates him to listen and to keep the orchestra alert.

The best can conduct and listen at the same time. Not only can they anticipate, they can respond. Claudio Abbado used to point with his left hand at the instrument to which he wanted his players to listen at any moment. He’d look around the players as if to ask “Are you hearing this?” and his performances seemed to be filled with love as well as music because of it.

Leave a comment