It’s one of the questions musicians hear from time to time. For those of us who work as performing musicians it’s an almost impertinent question because conductors, especially the good ones, carry the most responsibility of anyone on stage for the performance.

I heard a conductor answer the same question once by recommending to the person asking the question that they listen to two different recordings of the same piece. The difference between the recordings is some measure of what they do. It’s a good shorthand answer.

As composers wrote more complex music for larger orchestras during the C19th, the need arose for a director to organise and co-ordinate the performance process. The first people to define the central all-important job of the conductor were the composer-conductors – Louis Spohr, Hector Berlioz and Felix Mendelssohn. Then came the specialist conductors like Hans von Bülow (1830-1894) and Hans Richter (1843-1916).

The process of preparing and performing a full score (the big book that has all the composer’s annotated music and markings) starts long before the performance. First, if required, soloists will be selected and contracted with the artistic manager of the orchestra or the casting director of the opera company. This can happen years in advance for an opera. For a concert repertoire piece bookings happen later in the process.

An organised conductor will liaise months in advance of the rehearsals to confirm the distribution, the number of players in the string section, preferred section leaders, the minimum number of percussionists who can multi-task the specified percussion instruments in the score, and the layout of the orchestra – where instruments sit in relation to each other is an important precedent for ensemble. An extreme example of the need for a carefully considered seating plan can be found in Berlioz’s Grande Messe des Morts. There is a section in the Hostias where three high flutes have a duet section with eight trombones playing at the extreme lower end of their range. It’s a nerve-racking moment and can be painfully difficult to tune. If the trombones are too far from the flutes it makes the intonation all the more difficult.

The next part of the assimilation of the score is to specify bowing for the strings where it is not obvious. To get specific colours and emphasis from the strings it helps to mark in their parts whether the phrase is to be played starting with an up bow or a down bow, pushing or pulling the bow across the strings.

Not all composers balance the sound of their orchestras. Most conductors are unguarded about sharing their experience, observations and fixes with their conductor colleagues. They share solutions to problems of balance that composers wrote into their scores. A common solution is to temporarily reduce the number of string instruments playing at a delicate moment. The ranks of strings are divided into “desks”. A desk comprises two players sharing the same music stand. By reducing the number of desks playing at a certain moment, the conductor can effectively alter the balance.

The conductor will work with the orchestral manager to specify the number of rehearsals required for each part of the programme. Repertoire pieces require less rehearsal while new or rarely performed works will need more time.

Each piece has a different orchestration. The conductor has to specify which instruments are required for each rehearsal. Freelance musicians are paid by the rehearsal so it’s important for managements to book them for the minimum number of rehearsals possible for cost reasons. Strings will be required for most, if not all, rehearsals while a celeste player might only be required for one rehearsal. This part of scheduling is more knotty and detailed than you’d think.

All of the above usually has to be fitted around a busy performance schedule. Conductors often carry heavy bags of full scores to be studied and administrated for future appearances while on their travels.

If it is an opera, work with the singers starts four to six weeks before the opening night. This can be a fun, relaxed period of exploration and experimentation with ideas both for the staging and the musical preparation. In an ideal world, the stage director and the conductor work in consort to present something that looks and sounds cohesive. It isn’t always thus.

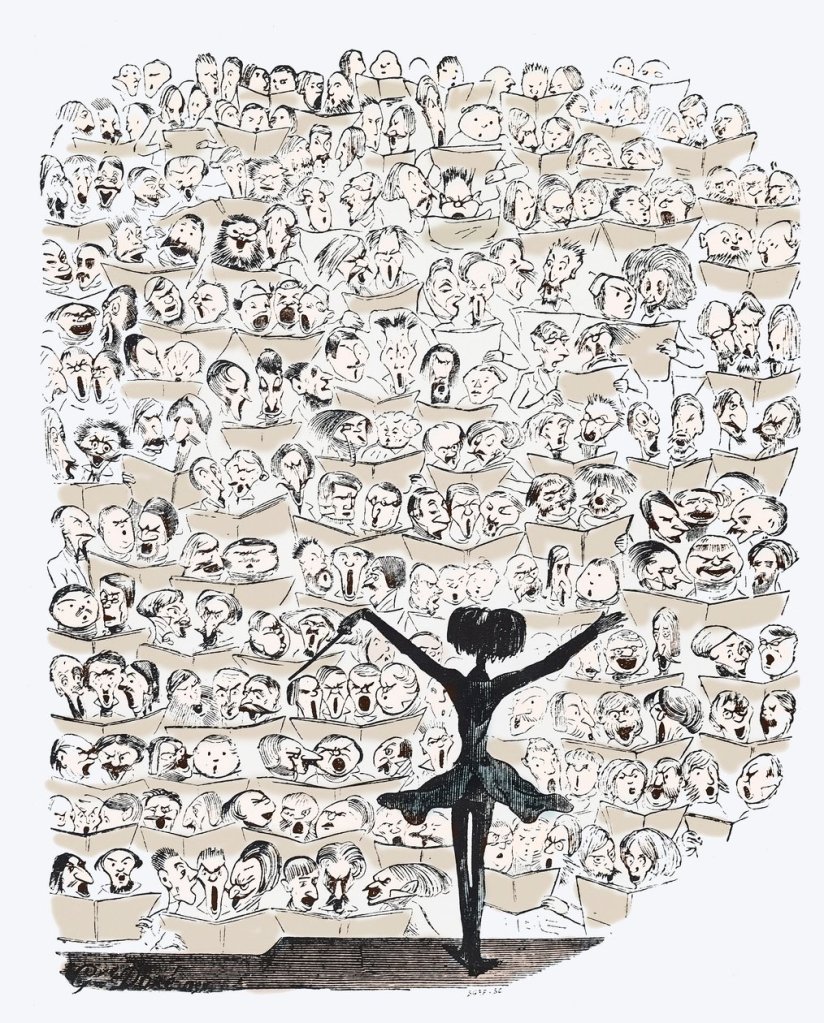

The first part of the rehearsal process with an orchestra is called the orchestral read through. It’s exactly what it says – the conductor leads the orchestra through the whole work for the first time. It’s the first step in the process of assimilating the score with the orchestra. Basics of tempo are established and challenging passages may be repeated. After that the conductor will have a rehearsal with the soloists, if so required. Then all the forces, including full orchestra, soloists and/or choir, are drawn together for tutti rehearsals which will take a day or two for a full programme. The last part of the rehearsal process is the dress rehearsal on a day before the first performance or on the day itself.

So far we’ve covered the rehearsal process. Tomorrow I will break down what a conductor does on the podium in performance.

Leave a comment