One of the many extraordinary and exciting things about classical music and the way we perform it is its durability.

The first violins in the form we know them today were designed and crafted by the master luthier, Andrea Amati of Cremona in 1564. Since then the only things to have changed in their structure are the strings (steel, as opposed to gut) and the mechanism with which we fine-tune the strings. After that, the instrument with which violinists from Paganini to Augustin Hadelich create colours, from exquisite sweetness to harrowing drama, hasn’t changed at all. Indeed, the finest soloists play on the very same instruments made by the master luthiers of Cremona all those centuries ago.

In a world where photographers update their cameras every year, where music producers update the software for their studios on a weekly basis, where gamers move onto the next console for its speed and graphics as soon as a new platform is released, I find it remarkable that an instrument made for the highest form of musical expression and virtuosity hasn’t been improved in all that time.

Even the design of a piano, perhaps the most complex and exactingly engineered instrument on the concert platform, hasn’t been significantly updated since the late C19th. That means when we attend a performance of a symphony or an opera, all the musical colour and range of expression that we hear, from thumping climaxes to delicate whisperings, is generated and projected without the use of electricity and instead maximising the laws of physics as known to Newton.

That fragile wooden box we call a violin projects all the warmth, lyricism and tenderness to thousands of listeners, throughout a huge concert hall by means of vibration and air alone. I find it miraculous.

Of course, composers have written many works that require electronic instruments. The combination of an orchestra with the unearthly force of the ondes martenot, an early electronic instrument, in Messiaen’s Turangalila Symphony is an example of acoustic and electronic music working together to great effect.

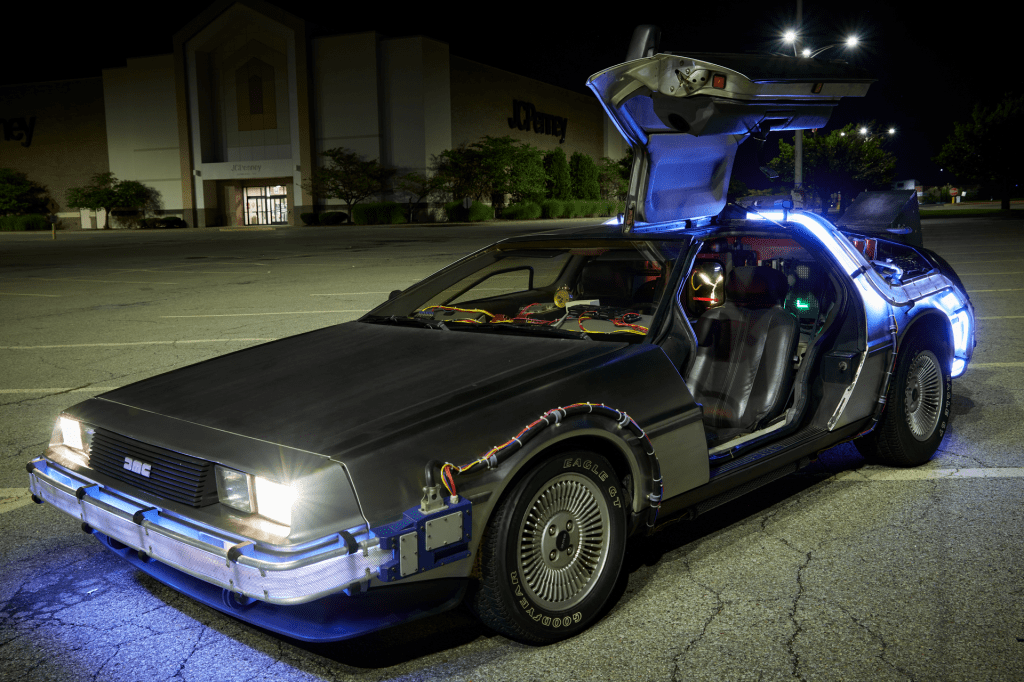

I think of music’s capability to transcend the need for technological updating as a refreshing escape from a world constantly on the lookout for “the next big thing”. I call it music’s Time Machine effect.

When I walk into a concert hall, a theatre or a church to hear a piece of music there is nothing in my experience of the sound today that has been added since the day it was written. When I take my seat to listen to Haydn’s Creation, I am effectively setting a dial to take me to 1799. And there in sound I experience the post-enlightenment understanding of the cosmos as Haydn describes the movement of shooting stars, gas giants and the formation of galaxies in sound.

There is barely any difference between my London experience in 2024 and that enjoyed by the Viennese audience at the old Burgtheater on 19th March, 1799 when it was first performed.

If I use my imagination as I listen, I can enter the mindset of post-enlightenment Europeans and wonder at the new understanding of late C18th scientists about our universe and heliocentricity; the new and fast expanding discoveries of where humans and Earth stand in relation to other planets; Captain James Cook’s journey to Tahiti on the other side of the world to observe the transit of Venus across the face of the sun during an eclipse in 1769. These exciting recent discoveries of the time seem to be translated into Haydn’s overture for The Creation.

For the duration of the concert I have the ears of someone in 1799. If I’m especially involved, I try to expunge all the musics in my head that were written subsequent to 1799 – go with me here. If I try to imagine what it was like to hear Haydn’s music without the music of Schubert or late Beethoven, Berlioz, Brahms, Wagner, Mahler, Stravinsky and beyond that lives in my head, I hear it for its visionary modernity. How thrilling to have the complexity and wonder of the cosmos described in such poetic and digestible musical terms for the first time.

These are some of the thoughts that cross my mind as I sit and wonder at Haydn’s creativity and his courage to sit at the vanguard of his known musics and make new music of his own that bears a direct relation to scientific discovery and our understanding of the universe.

It’s in moments like that when I think of music as my Time Machine every time I go to a concert.

Leave a comment