I will have to dig deep to write this one.

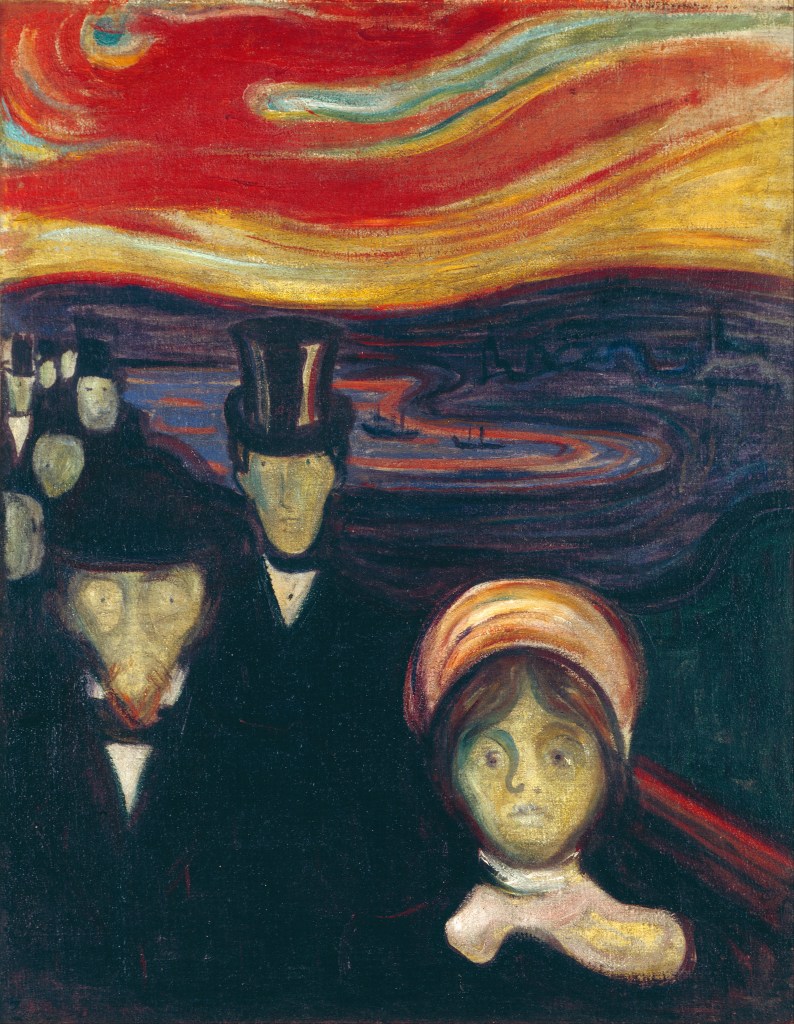

There are performancesf when I don’t feel particularly nervous beforehand. There are others when I would prefer the ground to open up and swallow me than walk out on stage. The latter performances are usually conditioned by forces outside my control.

Since I can remember, in the lead up to a performance, I live in a state of excited anticipation. The first time I sang a solo in public was when I was eleven. My whole life was consumed by the event and everything else went on hold. I worked myself into such a lather that by the time the concert came, I was exhausted and distracted. It was the Pie Jesu in Fauré’s Requiem, in case you were wondering. It passed by in a flash. Looking back on it, the change in me from before the song to afterwards set in motion an addiction pattern of anticipation – fear – exhilaration – satisfaction that I would seek to repeat for the rest of my life.

The next significant solo I sang was when I was fourteen. My voice had dropped to a baritone and I was chosen to sing The Three Kings, a carol for Epiphany, in front of my school in Sunday chapel. Again, I put my life on hold and began the cycle of obsession. The thought processes revolved around the same set of fixations for days in the run up. Will people like it? Will they like me more for it? What if it goes badly? What will it feel like to be the centre of attention for the whole school for a few minutes? What if I sing it better than it’s ever been sung before? Will I enter into some kind of immortal brotherhood reserved for the great? But what if I make a mess of it? And round and round I would go.

On the day, the school director of music saw me shuffling around on the chapel steps, nervously going over contingencies in my head. He saw the state I was getting myself into and sidled up to me. “You know, they only want you to do well.” Hallelujah!

I have recalled his words countless times since that January day in 1984. The comforting truth within them is that audiences want to enjoy themselves. I sometimes wonder what course my life would have taken without his wise, well timed intervention.

I went through a long phase of telling myself and others that I don’t get performance nerves. I was in denial and the effort that went into maintaining the lie went some way to having the desired effect of suppressing the negative effects. It was a version of “fake it to make it”, I suppose, but at the back of my mind I was always mindful of specific challenges.

At some point I acknowledged my performance anxiety cycle. I learnt to be objective about which factors lay within my control and those outside my control, like a sore throat, other people’s mistakes, things like that. The factors inside my control are preparation, sleep, avoiding unnecessary distraction, living a healthy life, looking after my mental health, sobriety etc etc.

It can happen that a colleague gets ill and I step in as a replacement. If I know the music well and the performance is a concert there’s nothing to worry about. However, I have been asked to replace people at the last moment in an opera production. A certain amount of improvisation and chutzpah is required to get through those nights. I remember one occasion in Munich, I was 26 and relatively new to the professional stage. I had performed the role of Idamante in Mozart’s Idomeneo at Welsh National Opera eight months previously. My agent rang while I was recording some Beethoven folk songs. He told me Munich State Opera had lost their Idamante for the performance the next day in their prestigious July festival.

I agreed a contract, finished my recording session and headed to Munich. On arrival at the theatre that evening, I was taken to a room with a television and a video tape player. I watched the video of the production and tried to translate what I saw to the dimensions and mirror opposites of a stage. The next morning, I woke up to discover I remembered nothing of what I had seen on that screen. I then had a studio session with one of the cast members. We went through the basic entrances and exits of the production, worked on the principle of a gun that came and went inexplicably in the conceptual staging – an idée fixe that never went anywhere.

I was asked If I’d prefer to work or rest in the afternoon. I chose to work for an hour with the assistant director and then went to my hotel to lie down. I didn’t sleep at all and instead went over and over what I could remember of the involved staging. I then headed to the theatre, put on my costume, received my makeup and waited in my dressing room for the call to come over the tannoy for me to make my way to the stage for my first entrance.

As the call came, there was a knock on my door. I opened the door to see a tall, well-built man in a powder blue uniform.

“Herr Spence, I am here to accompany you to the stage.”

“Let’s go.” I said.

He then placed a hand on my shoulder and took hold of my elbow with a firm grip. He walked me to the stage – to this point I had never set foot on the a stage of Munich Opera. He guided me round to the far side of the stage where my entrance would be. My dry throat tightened as I heard the soprano sing her lines before my entrance and on my cue the door to the enclosed set opened. The orderly in the powder blue uniform then placed a hand on my back and pushed me through the doorway. On my first appearance to the Munich audience I must have looked startled.

I asked afterwards about the big man in the uniform. It was explained away as a precaution that the opera house took as a matter of course with stand-ins since a replacement tenor had bolted in fear at the last minute on one occasion. The performance had to be cancelled and the audience were reimbursed.

Munich was my first and last brush with extreme anxiety. Over the years I have developed techniques to help mitigate the negative effects of performance anxiety.

1. Meditation helps me objectify obsessive cyclical thinking. Accepting negative thought processes are part of the performance experience was a significant step forward for me.

2. Prioritising sleep.

3. Be punctual. Allow plenty of time to get to the venue but don’t arrive too early. Milling around with nothing to do can be unsettling.

4. No alcohol the night before the performance.

5. At the side of the stage, before my entrance, I remember my director of music at school saying the audience wants me to do well.

6. The last thing I do is keep in mind that something might go wrong and if it does it won’t matter. Singing is not brain surgery.

Leave a comment