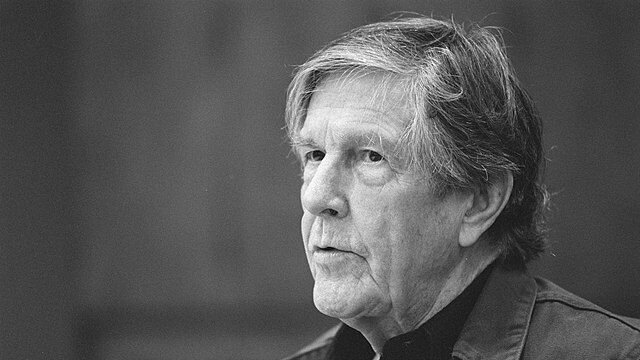

John Cage

Why do we call it “classical”… Part 2

The problem with the word “classical” in relation to music is that it comes freighted with specificity. As I explained yesterday, the word was originally applied to music that adhered to strict standards of structure and tonality from 1750 to about 1830 – N.B. roughly the same dates as the Industrial Revolution.

Of the broad classical music genre, only a small percentage of the canon can be accurately termed “classical”. It wasn’t long after 1830 that composers became increasingly experimental. Berlioz wrote for new distributions of instruments and started to write long, sinuous melodies that stretched far beyond the metered four bars of the melodies during the classical period. Liszt wrote programmatic instrumental music that followed a narrative for its form, deploying thematic variation for nuance.

Wagner, a protégé of Liszt, said he couldn’t write music that didn’t have a story to tell. He somehow fabricated a new kind of music and tailored it for the specific mood in each of his operas. In Tristan und Isolde, his most tonally adventurous work, Wagner more-or-less abandoned the established rules of harmony altogether to explore the human emotions of erotic love, betrayal and guilt (I will expand on this in another blog). Until Wagner came along, clashes between neighbouring notes were expected to be resolved immediately from a dissonance to a consonance, in which the notes making up the harmonic chord are spaced and pleasantly balanced to the ear.

Arnold Schönberg, later in the C20th, credited Wagner with the “emancipation of the dissonance”. By that, Schönberg meant Wagner found a sound world in which dissonant chords no longer begged to be resolved in order to make harmonic sense. Already, in 1865, we are a long way from the classical ideals of Haydn and Mozart.

In 1902, Schönberg heard Debussy’s treacly new sound world in Pélléas et Mélisande. Pélléas itself was Debussy’s own riposte to Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde after hearing it for the first time in 1887. Schönberg set about writing his vast symphonic poem Gurrelieder while, at the same time, Stravinsky was writing Le Sacre du Printemps. Simultaneously, in the Paris and Vienna of 1911, the rules of harmony and structure, held to be sacred and unshakeable to that point, crumbled and collapsed as both works received their scandalised and now celebrated first outings.

Some people couldn’t stand the lack of harmony in the modernist sound world. During the Third Reich, the Nazi Party called it “Entartete Musik” or degenerate music, a label they attached to any music that did not align with their ideology, including works by Jewish composers, modernist music and jazz.

Lagging behind the societal shift from court to city during the Industrial Revolution, music no longer bowed to the authority of monarchy. It had become an act of revolution in itself and served its purpose to shock anyone who clung to old ideologies for self-serving purposes.

The revolutionaries were ever more brazen through the second half of the C20th. In America, John Cage sought to tear down all the preconceptions anyone might have of what music is. The Darmstadt School of Pierre Boulez, Luigi Nono and Karlheinz Stockhausen were unequivocal and renounced music that wasn’t provocatively avant-garde. And so it went on until the present day.

I hope you’re still with me, reader. I also hope you see where I’m going with this potted history of musical developments from the classical era to the modernist era. Tomorrow I will consider alternative terms that work for all musics in the genre known as “classical”.

Leave a comment